A timetable for ending QE

Dr. David Kelly, CFA

Managing Director

Chief Global Strategist

Anthony M. Wile

Market Analyst

Global Market Strategy Team

In a press conference following this week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, Ben Bernanke, chairman of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed), provided markets with a clearer understanding of how the Fed expects to phase out its current quantitative easing (QE) programme. This timetable is justified both by economic progress and by the significant future costs that a too-large Fed balance sheet is likely to entail. Moreover, the timetable, while never previously explicitly outlined, should not have been a surprise to most market observers. Nevertheless, Bernanke’s words have been met by a sharp selloff across a wide range of financial assets. For investors, it is important to distinguish between logical market reactions and over-reactions, while still positioning portfolios for an environment of rising interest rates.

A clearer message from the Fed

At 2:00pm on Wednesday 19 June 2013, following a two-day policy meeting, the FOMC released its usual short statement on monetary policy. Few words were changed in the statement (compared to the statement from the previous meeting) except for a recognition that risks to the outlook for the economy and the labour market had ‘diminished since last fall’. This was actually quite significant since the latest version of QE, the monthly purchase of USD 85 billion in Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, was initiated last autumn.

At 2:30pm , in an opening statement to his post-FOMC meeting press conference, Bernanke provided far more clarity on the Fed’s thinking by enunciating the Fed’s expectations on both when it would begin to phase out QE and when it expected to complete the phase out. In particular, Bernanke noted:

‘If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year; and if subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear. In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7%, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains – a substantial improvement from the 8.1% unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this programme.’

Bernanke also made it clear that the Fed did not intend to raise the federal funds rate from its current 0-0.25% range, until the unemployment rate was at least down to 6.5%.

Why QE needs to be phased out

It needs to be said that a timetable for ending QE is far easier to justify than the programme itself. The current QE programme combined with a near-zero federal funds rate, amounts to the most extreme dose of monetary stimulus applied by the US Federal Reserve in its 100-year history. With the economy in its fifth year of recovery, unemployment down 2.4% from its peak, home prices and stock prices up sharply over the past year and financial stress clearly much lower than a few years ago, it is hard to justify such an extreme approach. It is also unlikely that this monetary ease is really helping growth. In fact, by reducing the income of savers, discouraging lending by artificially lowering long-term rates and convincing people that they don’t need to borrow ahead of higher rates, recent monetary policy may have been more of a drag to the economy than a boost.

Equally importantly, the Fed’s fast-expanding balance sheet carries dangers of its own. Up to this point, the Fed has increased the size of its balance sheet without causing a surge in the money supply by paying banks interest on the reserves they hold with the Fed (as opposed to lending out to the private sector). However, this also implies that in order for the Fed eventually to raise the federal funds rate, it will need to increase the interest paid on reserves in tandem.

The problem is that even if the Fed sticks to Bernanke’s timetable, banks would be holding a projected USD 2.5 trillion on reserve with the Fed by middle of 2014. If the Fed over the next few years raised the federal funds rate to a roughly ‘neutral’ level of 4% (roughly 2% higher than core inflation), the 4% interest that it would then have to pay on bank reserves would cost USD 100 billion per year, which could leave it in a net negative income situation. If it tried to avoid this by selling bonds and shrinking its balance sheet it could push long-term interest rates to spike. Conversely, if the Fed postponed rate hikes altogether, it could set the economy up for inflation. The bottom line is that the bigger the Fed’s balance sheet gets, the more expensive it will be to maintain and the more disruptive it will be to dismantle. The Fed knows this, as should those who watch the Fed. While Bernanke’s announcement of an explicit timetable for ending QE surprised markets, the timetable itself should not have.

Market reactions and overreactions

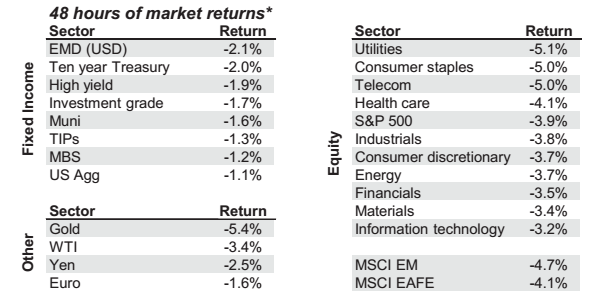

Since these announcements, as can be seen in the table below, global fixed income, equity and commodity markets have seen sharp selloffs. However, it is important to distinguish between those market movements that are justified by the Fed’s actions and those that are not.

*Performance represents price return only between market close on 18 June 2013 and market close on 20 June 2013.

*Performance represents price return only between market close on 18 June 2013 and market close on 20 June 2013.

For the most part, the selloff in fixed income markets seems justified. Between the close of business on Tuesday and the close of business on Thursday, the yield on ten year Treasuries rose by 24 basis points. Even with this, ten year Treasuries on Thursday were yielding 2.42% compared to a year-on-year core CPI inflation rate of 1.68%, resulting in an ex-post real yield of 0.74%, far below the average real yield of roughly 2.5% seen over the last 50 years. Other areas, such as high yield bonds, saw bigger losses, partly in reaction to the equity market movement. However, in a normalising economy, real interest rates still have a long way to rise to get to a ‘normal’ level.

For the stock market, the overall reaction seems extreme, with the S+P 500 losing twice as much in two days as the ten year Treasury bond. It should be noted that, by laying out a path to ending QE, Bernanke has not increased uncertainty – he has reduced it. It should also be noted, as the Fed chairman repeatedly did in his news conference, that this timetable is data dependent. The Fed can keep QE around longer, (and thus, presumably, maintain low long-term interest rates) if it believes the economy needs it.

Sadly, the Fed may now be the victim of its own rhetoric. Having spent years over-hyping the benefits of QE, it appears to have convinced some market participants that the economy can’t get by without it.

This is very likely to be wrong. The US housing market is in a firm recovery and, even with somewhat higher mortgage rates, overall housing affordability will remain far better than in recent decades. While fiscal drag has hurt the US economy in recent years, there is little likelihood of further significant federal tightening over the next few years, while state and local government employment is now beginning to rise. Most importantly, a move toward more normal interest rates should help convince many businesses and consumers alike that the economic crisis is over and reduce the hesitancy to act that is always the most pernicious aspect of a weak economy.

Over the next few months, this should become clear and equity markets should reflect this. In the meantime, it is important for investors to continue to position their portfolios for rising interest rates, with a tilt towards growth equities and away from longduration, high-quality fixed income.

The Market Insights programme provides comprehensive data and commentary on global markets without reference to products. Designed as a tool to help clients understand the markets and support investment decision-making, the programme explores the implications of current economic data and changing market conditions.

This document has been produced for information purposes only and as such the views contained herein are not to be taken as an advice or recommendation to buy or sell any investment or interest thereto. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the reader. Any research in this document has been obtained and may have been acted upon by J.P. Morgan Asset Management for its own purpose. The results of such research are being made available as additional information and do not necessarily reflect the views of J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Any forecasts, figures, opinions, statements of financial market trends or investment techniques and strategies expressed are unless otherwise stated, J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s own at the date of this document. They are considered to be reliable at the time of writing, may not necessarily be all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. They may be subject to change without reference or notification to you. Both past performance and yield may not be a reliable guide to future performance and you should be aware that the value of securities and any income arising from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions. There is no guarantee that any forecast made will come to pass.

J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the brand name for the asset management business of JPMorgan Chase & Co and its affiliates worldwide. You should note that if you contact J.P. Morgan Asset Management by telephone those lines may be recorded and monitored for legal, security and training purposes. You should also take note that information and data from communications with you will be collected, stored and processed by J.P. Morgan Asset Management in accordance with the EMEA Privacy Policy which can be accessed through the following website http://www.jpmorgan.com/pages/privacy.

Issued in Continental Europe by JPMorgan Asset Management (Europe) Société à responsabilité limitée, European Bank & Business Centre, 6 route de Trèves, L-2633 Senningerberg, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, R.C.S. Luxembourg B27900, corporate capital EUR 10.000.000.

Issued in the UK by JPMorgan Asset Management (UK) Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England No. 01161446. Registered address: 25 Bank St, Canary Wharf, London E14 5JP, United Kingdom.

To learn more about the Market Insights programme, please visit us at

www.jpmam.com/insight